It must have been the last quarter of my junior year of high school. That time of year when high school seniors start thinking of a college course. So I wrote my Dad in Bangkok about my plans. I told him I was choosing between history or economics, my favorite subjects in high school. There was no indecision about the choice of university. It would be the University of the Philippines, where everybody in the family went, except my Mom who graduated from the University of Sto. Tomas.

In answering me, my Dad completely disregarded the other option — i.e. history — and fully focused on the merits of an economics degree. On hindsight, his recommendation was life defining. I graduated with honors, addressed the graduating class and immediately was hired by the Development Academy of the Philippines to elaborate on my dissertation research on the measurement of Philippine poverty.

And I find myself today, reading on Philippine economic history of the 50’s. This is really just for my Dad’s and I guess, also my family’s benefit, since in university I never took this subject seriously. Funny, how the past haunts you long after.

To recall, Frank Golay who wrote on Philippine industrialization. The post-war Philippine economy was a period of rapid expansion, a pattern that continued till the mid-sixties. Prices were stable and national production expanded for about 56%, averaging about 7% a year. This expansion included both the agricultural and manufacturing sectors. Growth in manufacturing was quadrupling, largely explained by high levels of government economc activity and capital formation. There was also the tremendous infusion of foreign capital – US aid and reparations inflows.

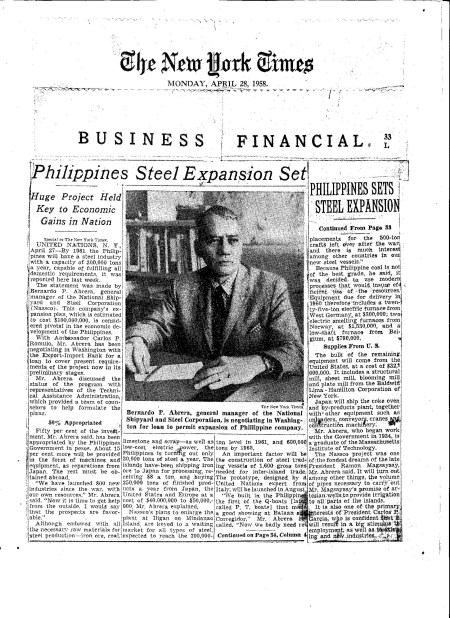

Government was a tremendous presence in economic life. In the early 1950’s the government was operating railroads, hotels, electric power, gas, waterworks, as well as producing coal. cement, fertiliser, steel, textiles, yarns. It had investments in manufacturing incandescent bulbs, pulp and paper. There was a national bank (PNB) and a national airline (PAL). Among the manufacturing enterprises government established were the prestige investments – the shipyard and the steel mill.

These government investments were important measures to build the people’s hope for the future. Consider a young republic seeking to rebuild the economy post war and eager to demonstrate its independent capacity and abilities. With a band of U.S. trained technocrats, the government was seeking to spread its wings and jumpstart national ownership and entrepreneurship.

All these efforts posed a threat to the long-standing dominance of established elites. Almost as soon as post-war rehabilitation began, complaints against government enterprises started with venomous charges of corruption, nepotism and inefficient management. Seeking to dampen the criticism, the government launched several initiatives to encourage “new and necessary” enterprises that would help restore pre-war industries. It included tax incentives, these new industries were exempt from paying taxes for four years and more, then controlled foreign exchange allocations were allocated to subsidize industrial development. These incentives backfired. Filipino entrepreneurs sought economic advantage through political institutions and processes. Many of the apparently well-developed political, legal, and bureaucratic institutions had shallow roots and could be easily manipulated by powerful political-business oligarchs. Soon, there were unrecedented levels of imports, financed by high levels of the United States disbursements under War Damage Payments and other programs. The private sector enjoyed windfall profits and this path to undustrialiation proved unsustainable.

Interviews forthcoming

Leave a comment