President Rodrigo Duterte delivered his State of the Nation (2020) address yesterday afternoon. He started with a tirade against the media giant (ABS-CBN) he had successfully shuttered then cresendoed to personal attacks on many others: the opposition, the so-called “oligrachs”, the water concessionaires and all those who have ever criticized him. He rambled. His only words for praise were for the ubuquitous senator/aide, Mr. Bong Go and Mr. Go’s “malasakit” centres (very few know what caring they give and where they are). Oh, he reassured us that we “lost” the West Philippine Sea but no worries, he talked to President Xi about having Chinese vaccine against the virus. Mr. Duterte had no words of sympathy for our beleaguered health workers, nor for the hundred of thousands stranded in Metro Manila’s cramped stadiums, nor for that matter, the millions who have lost jobs. There were no words of encouragement to the micro and small businesses struggling to survive. After more than an hour, he ended this tiresome speech by justifying his infamous drug war and renewing a call to reintstate the death penalty. The speech was a mess. The insensitivity was heartbreaking.

I am almost glad that my father isn’t around to hear this speech. Though I miss him (and actually think we could be having really great conversations in this time of my life!), I would spare him the sorrow. How terribly dissapointing this would have been for a man who passionately loved his country and was committed to its future. He, who had dreams of a prosperous country and an energized people rebuilding from the ravages of a world war and foreign rule. He, with his pursuit of excellence (“if you want to be a garbageman, be one. But be the best garbageman, ever”) and his impatience with mediocrity (“Baltik” was his nickname).

Disappointing though it might have been for him though, I doubt if he would have been disheartened. I have a sense that he would have kept faith in his people and in his country. Because that was just the way he was.

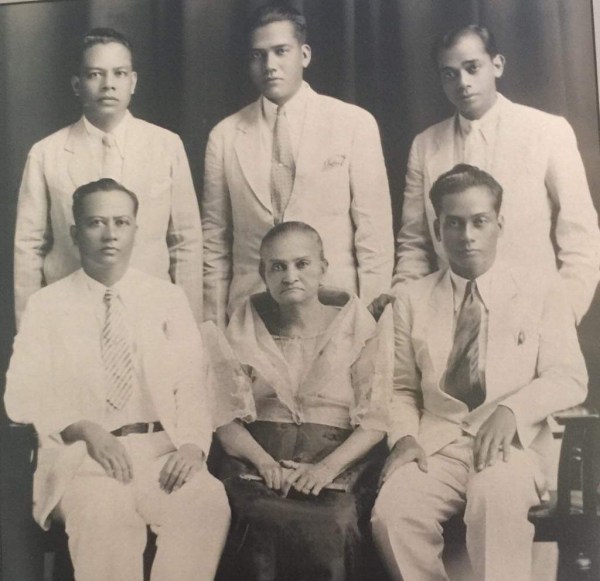

My father knew about struggle. Born poor, the youngest of five children, Bernardo came from the smallest of small Philippine barrios, where men and women raised food in small farms, caught fish in small boats and lived/died in the same house where they were born. And yet he kept going. He left his hometown for higher grade levels and bigger schools in far-away bigger towns. He became a domestic worker, in exchange for a chance at high school. He took on restaurant dishwashing, at the height of the American depression. But by kind destiny, he had a mother who nurtured his ambition and an American mentor who believed in him, his intelligence and his integrity.

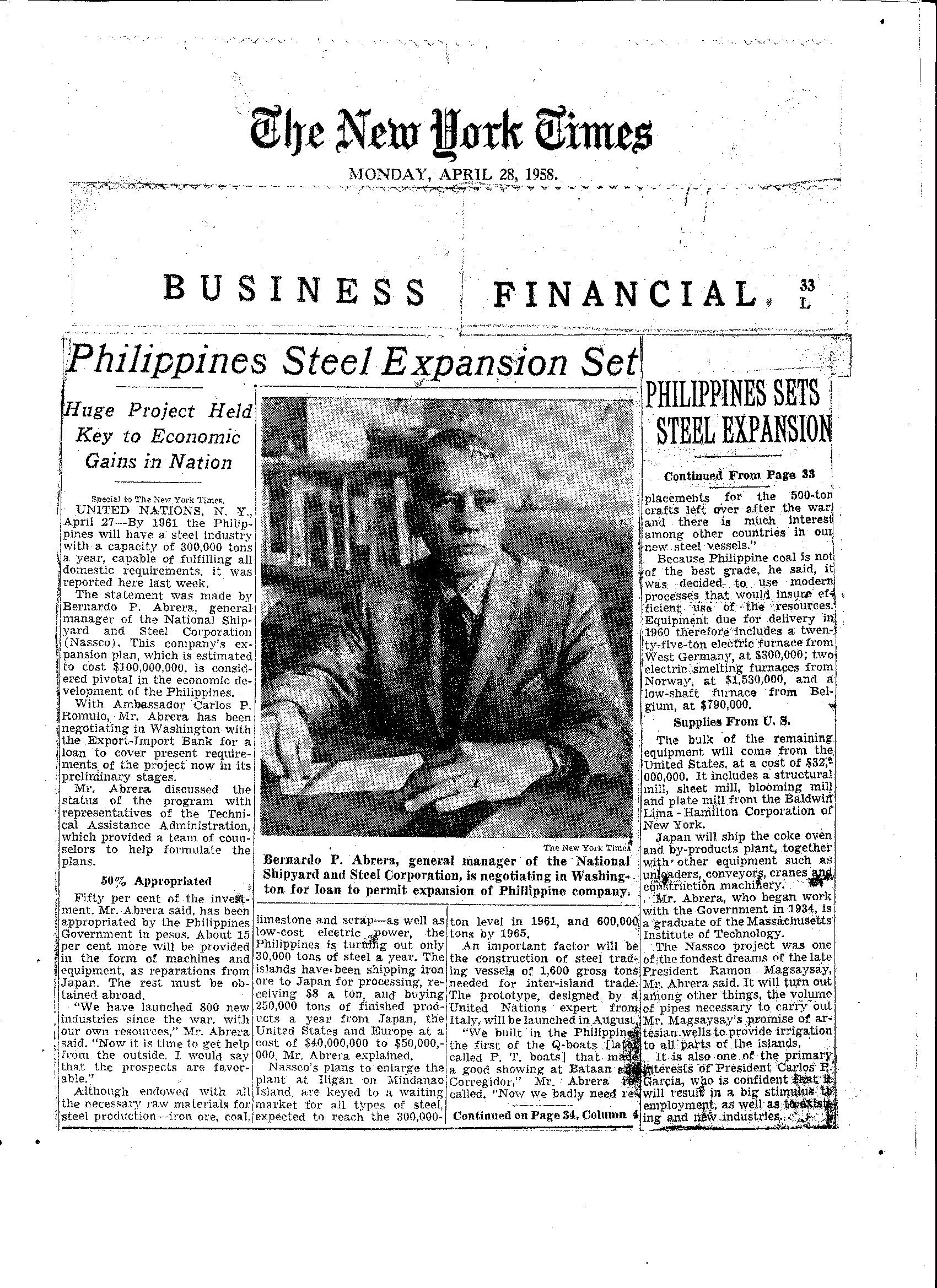

And he knew about winning against all odds, despite the ups and downs. The little Q-Boat he built just before the war survived foreign models and enemy fire; the patrol boat ferried MacArthur and Quezon to safety. Under my father’s watch, the country built its own ships. To support long-term shipbuilding, again under his watch, the Iligan Steel Mill was established. And with both, the spill-over employment and income effects built the local economies of Mariveles in Bataan and Iligan City in Mindanao.

Philippine-made ships and Philippine Steel are a testament to his vision, a nod to his persistence and to his integrity. Getting both done is a testament not only to his intelligence but also his grit. In a newly discovered file of the American Chamber of Commerce in 1947, an extended report covers the demands on my father to justify the selection of an established reputable contractor over an unsuitable late-comer endorsed by a politician. If I know my father a little, he would have been exasperated by these episodes. Yet he kept on.

Bernardo’s story goes beyond the story of ships and steel. His narrative teaches me to keep faith and keep going despite today’s darkness. His life reminds me: dreams matter; dogged perseverance matters; love of country matters. Though today, our ships and steel are mainly from China, once upon a time, we proudly built our own, equal to to the world’s best. Against all odds.

My country’s story is not yet finished. We have had our share of strugglies, victories, and falls into despair. And yet somehow, we rise up, again and again. And someday, it will all be good. Like Bernardo, we must keep the faith.